A self-proclaimed minimalist and a repressed man walk into a bar

... and they're the same person

I was hanging out with a close friend, sharing stories and recent life events, and the conversation somehow turned to how friends and people in general (sometimes including myself) become selectively identityless in certain aspects of life to avoid certain harsh realities and realisations therein, and it got me thinking. I’ve seen exactly this behaviour in many around me, and it’s been interesting to understand why this might be the case.

What this post is not

It is not about self-identity or finding ways to build it. It’s about its lamer cousin, identitylessness, and to an extent, the perils of cowering behind it. I can also assure you the rest of the post is not some story about discovering how you should be “not-boring” as a person (lol). I’d say it’s more about unearthing why certain behaviours give rise to others that may seem highly unrelated, but have similar flavours and consequences if left unchecked. And no, I am not having a quarter-life identity crisis.

I grew up a staunch minimalist.

Ask anyone close to me in college and they’d say my biggest flex would be “he can move out of his dorm room in less than an hour if needed”, while others would take hours or even days. I assumed having more things would just get in my way, so I brought only the essentials. My friends, on the other hand, would bring colorful tapestries, blu-tack photo walls, carpets, posters, fairy lights, espresso machines1 (???) – and oh boy, I’d have this silent, almost-cringe-like expression when visiting their rooms for the first time, but of course, it wasn’t personal or a big deal; to each their own.

I moved around quite a bit growing up, so the concept of “home” was always distorted (I’ll spare you the usual third-culture kid sob story). My dad loves collecting things – crockery, trinkets, electronics, books – and would even occasionally dumpster-dive and upcycle not-so-worn-out things into random showpieces. Mum would semi-jokingly chide, because she knew having many things at home just meant any potential move would be even more annoying2. She’d also occasionally tell me things like “don’t do this when you have your own house, it’s a pain in the neck to maintain.”

Somehow, unintentionally, being minimal sounded very appealing. It came with a certain sophistication and was less of a headache. Being minimal was easy, and soon, anything that didn’t meet my almost-vague internal standards of “minimal” was immediately perceived as “doing too much” or sometimes, even cringey. Again, it was never personal but it’s one of those “couldn’t be me” type situations.

Aesthetic Minimalism vs Mental Minimalism

I’ve come to realise a person’s interest in (or disdain for) minimalism can manifest in many ways shaped by the circumstances they grew up with. I began to view innocent abundance, like collecting things and memorabilia, as silly and lame; comedically, I even went as far as calling such things “dust-catchers”. My evergrowing need to seek minimalism around me became a crooked mental model of its own, with this behaviour of believing less is more accidentally and latently seeping into aspects of life itself.

Of course, it always begins with the harmless aesthetic aspects: following minimalist interior design accounts on Pinterest and YouTube, scanning through the latest IKEA catalogue when it was mailed home, and keeping an eye out for “minimal” homes and cafes when on walks. And yes, I genuinely do think these things are easy on the eyes, and I’d enjoy living in such spaces. I call this aesthetic minimalism. At the meta level, aesthetic minimalism entails not taking “less is more” literally: it’s a celebration of the sophistication and purity that come with the selective emptiness. Choosing to be one is fine and good3.

The same “less is more” argument does not work with people. A deeper throwback revealed tiny hints of the seepage: the way I’d avoid expressing strong opinions, the way I’d avoid confrontation (which really was just intentional ignorance), or the way I’d sometimes resort to this weird negative-utilitarian way of seeing things when confronted by someone else. Depending on who you ask, they’d say these are pretty neat and Gandhi-esque; I surely thought it was me being diplomatic. But of course, these things tend to come off as cold and almost robotic, as if I move through the world without a care (when I really do, I promise!). There’s also the possibility of these behaviours being born out of a habit of not wanting to step on peoples’ toes or seem inconsiderate; this might be also be a side-effect of growing up without rich platforms to express oneself emotionally (among other possible causes). I view all of these behaviours as subconsciously choosing to be a mental minimalist.

In many ways, this is exactly what identitylessness is: you choosing not to care about, or want, something for yourself that is good for you because you think it’s either unattainable or not that important (when it really is). There isn’t any strong disposition to want to address it either because you’re conditioned not to care too much about such things (ie, caring about it more == making it a big deal == doing too much == not minimal). And perhaps life itself has been kind enough not to screw you over for not wanting to fix it.

In fact, folks my age would describe it best with “ya boring”. In much the same way I’d consider non-minimalist things as “doing too much”, certain feelings and deeds (eg: self-justice, confrontation, strong opinions) also came off as doing too much, so I avoided it, not because I was particularly scared (in fact I thought it was a show of strength) but because I didn’t care enough to want it for myself.

And sure, on a good day, I’d like to (humbly) think I have some “identity” going for me: I do all this fun research, I read about a lot of random things and love writing, I’m surrounded by people who love me, I meditate and do some mind-body stuff (don’t want my biases showing, do we?), I have better self-control as I age, I love meeting new people both online and IRL, I have fun (communal and personal) hobbies, and the list could go on at the expense of seeming like I’m tooting my own horn. But then again, if you’re being ultra pedantic, all of these increasingly start to sound like things I do, not am.

Mental minimalism is anti-life

It does make me wonder about the other direction: did my interest in so-called minimalism stem from my selective identitylessness? Of not wanting to seem chalant4? I don’t think so; it surely stems from believing I’m “doing too much” in certain areas of life where I actually should be. I felt unsafe being and doing too much. And perhaps it could also be chalked down to a mixture of other factors, but I digress. Don’t get me wrong: minimalism, in itself, is a great lifestyle choice – one that’s born out of simplicity, clean edges, order, and function. In its perfect form, it asks you to seek tiny happinesses from less.

Here’s where I think self-proclaimed (or accidental) mental minimalists get it absolutely wrong:

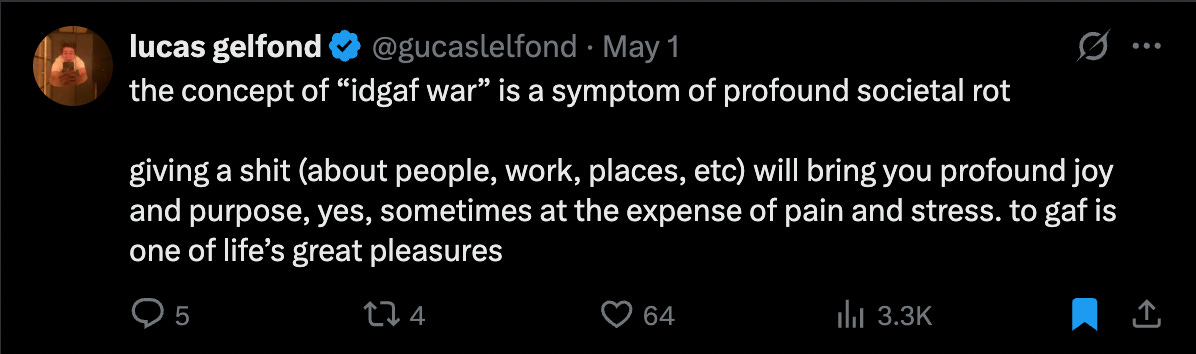

Mental minimalists think staying identityless in certain aspects of life allows them to traverse moral gray areas, show extreme empathy, and allegedly remain unbothered when things get tough in life; it’s a form of self-sacrificial non-chalance. But really, it’s all just cope and a form of pacifism and quietism (in its call to abandon your will and passively live life) because it’s the same people who may not have strong sense of self-justice, cannot stand up for themselves and let people walk over them, and risk having their boundaries violated because they’ve been conditioned not to care even if that happens. In the worst case, I’ve seen the same people get pretty slimy or express non-chalant views about pressing matters just to seem cool or “fit in”. I guess everyone wants to feel a sense of belonging but exercising selective identitylessness is also exactly where peoples’ inherent biases seem to glaringly show the most.

Choosing to be a mental minimalist will only give you more angst about who you really are underneath it all, because the emptiness clearly shows how much you failed to fill up within you despite having many opportunities in life to do exactly that.

When someone else projects their thoughts, emotions, and feelings at you, they expect something equally profound or relatable in return – and when you minimally respond with something that’s very on-the-fence, it comes off as apathetic, fake, or disingenuous, and that’s exactly why mental minimalists are seen as “boring”5. Obviously, this is not profound or new information in any way. The “weirdo” in the friend group will always other himself regardless of how highly he thinks of himself.

Disclaimer: I don’t think anyone actively strives to be a mental minimalist per se. It’s the sum total of life experiences that invisibly might compel someone to yield themselves to becoming one over time. It takes some careful mental gymnastics to undo it, but once done, allows you to live in a way that’s cool, low-angst, and desirable (which is kinda what any 20-something-year-old wants tbf).

Also, aesthetic and mental minimalism do NOT form a dichotomy where you get to pick where you stand. You can be an aesthetic minimalist while also having hints of mental minimalism (a lot of people do). Regardless, you choose to be either, with the latter obviously being at your own peril. Much like Heidegger’s concept of Geworfenheit, you can also choose not to be a mental minimalist when thrown into different situations in life that expect you to yield.

Identity-maxxing

I think this whole self-identity thing is an overblown object made up by Big Sad® to sell more hobbies and personalities to make you believe you’re normal and can fit in.

As long as you stand up for things you know to be good for you, you’ll never be “doing too much”. As long as you remain someone with upstanding character, you should feel more, do more, think more, emote more, object more, stand up more, and chalant more. This is the only remedy to mental minimalism and selective identitylessness.

This brings me to a different mental model: your identitylessness is increasingly reduced by all the ways you can fully express yourself to give yourself what is good for you. Your actions (your responses, tendencies, activities you do, etc) may just be means to express yourself, but acknowledging the meta-lessons, advantages, clarity, and takeaways from said actions are what’s good for you – and you should do more of them to eradicate identitylessness. I guess that’s also how you can be less boring6.

It’s easy to conflate identity (or identitylessness) with personality (or lack therof). More often than not, having a strong sense of identity comes with a great personality (case study: my amazing friends!), but it’s possible to have a lot going for you in the personality department but remain an empty vessel identity-wise; many names (including mine) come to mind on both fronts. Doing many things (activites) is also not a clear indication of identity or identitylessness. It’s also easy to believe that identity and identitylessness fall under a careful balancing act – one where you decide how much of both you can live with harmoniously on a daily basis. This is dangerous: for a while growing up, under the flawed world model of mental minimalism, I tried balancing both, only to realise the latter cannot and should not exist. The mind should never be allowed to tend towards minimalism, unless purely aesthetic.

If you think you have a tinge of selective identitylessness because of unfortunate circumstances in life, unless you start to “fill the emptiness”, anything you tell yourself about your self-identity will always feel performative or incongruent. None of it will ever jive with who you really are (or aren’t), and you’ll spend your time blindly soul-searching without much success. OR, you’ll remain comfortable in your identitylessness until you’re hilariously humbled by situations that betray those very sides of you.

I don’t want to make this blogpost any longer by talking about identity-building; greater men than me have tried (and succeeded!). So I’ll just leave you with one such nice attempt by a close friend, Sarv, who thinks identity is the sum of stories you tell yourself about yourself – and I agree. As a fellow third-culture kid, we’ve had a disgusting number of conversations about it ;)

I remember one such fella even started a tiny food catering service out of his dorm room in junior year. He’d make quick meals, cafe-style coffee, and snacks, and would sell it to us at decent rates. He became an internal sensation, selling out almost everyday. That dude was really living it up …

Nonetheless, I’m sure their goal was to fill the house with as much “life” as possible, perhaps an escape from everyday mundanity.

Looking at intentional empty spaces definitely brings a sense of calm because you can either take it for what it is, or project your own emotions, feelings, and thoughts on it without expecting anything in return.

I still find it funny how chalant isn’t really a word. It definitely should be. I love using it!

Looking back even more, I’ve seen similar patterns of selective identitylessness in many friends who have immigrant parents. Their parents had to go and do what they were told for the betterment of the family (not to be reductionist, of course). On average, there was barely any time for self-expression or avenues to figure out what they liked, bar simple pleasures that are identity-agnostic (like enjoying watching TV shows, buying the occasional IKEA potted plant, cooking, or going for walks). The parents probably put the kids in random classes and programs growing up, and eventually, most of these are given up. Continuing to be raised in families where there’s no overt need to expand one’s horizons beyond 1) what one does for work and 2) what one does for education only leads to further mental minimalism.

By less boring, I don’t mean doing a ton of cool activites. Someone can do just one thing really well, and as long as the actions therein allow them to express themselves and extract what’s good for them, there’s lower rish of being selectively identityless.