Indiscriminately seek the goodness in things, please

Being hopeful helps you ignore the "evil" in the world ... kinda

I’m in SF this summer! I love the energy, the people are amazing, and there’s so much to learn. I finally have time to think about “thinking” itself, among other things. I hope to spend the time writing more about exactly that, documenting my thoughts and connecting seemingly random topics together.

Preface

Something cool and admirable I’ve noticed in many lovely high-agency friends is the constant disposition to seek the inherent good in people around them, regardless of the latter’s odd behaviours, eccentric traits, obsessions, and weird tendencies that may provide evidence to the contrary. It’s very easy to avoid people after noticing something about them you don’t like, perhaps, in hopes of “protecting your peace”; there’s the usual argument of “it says more about you than them”. There’s an artistic integrity to doing otherwise and to engage with them as you would any friend.

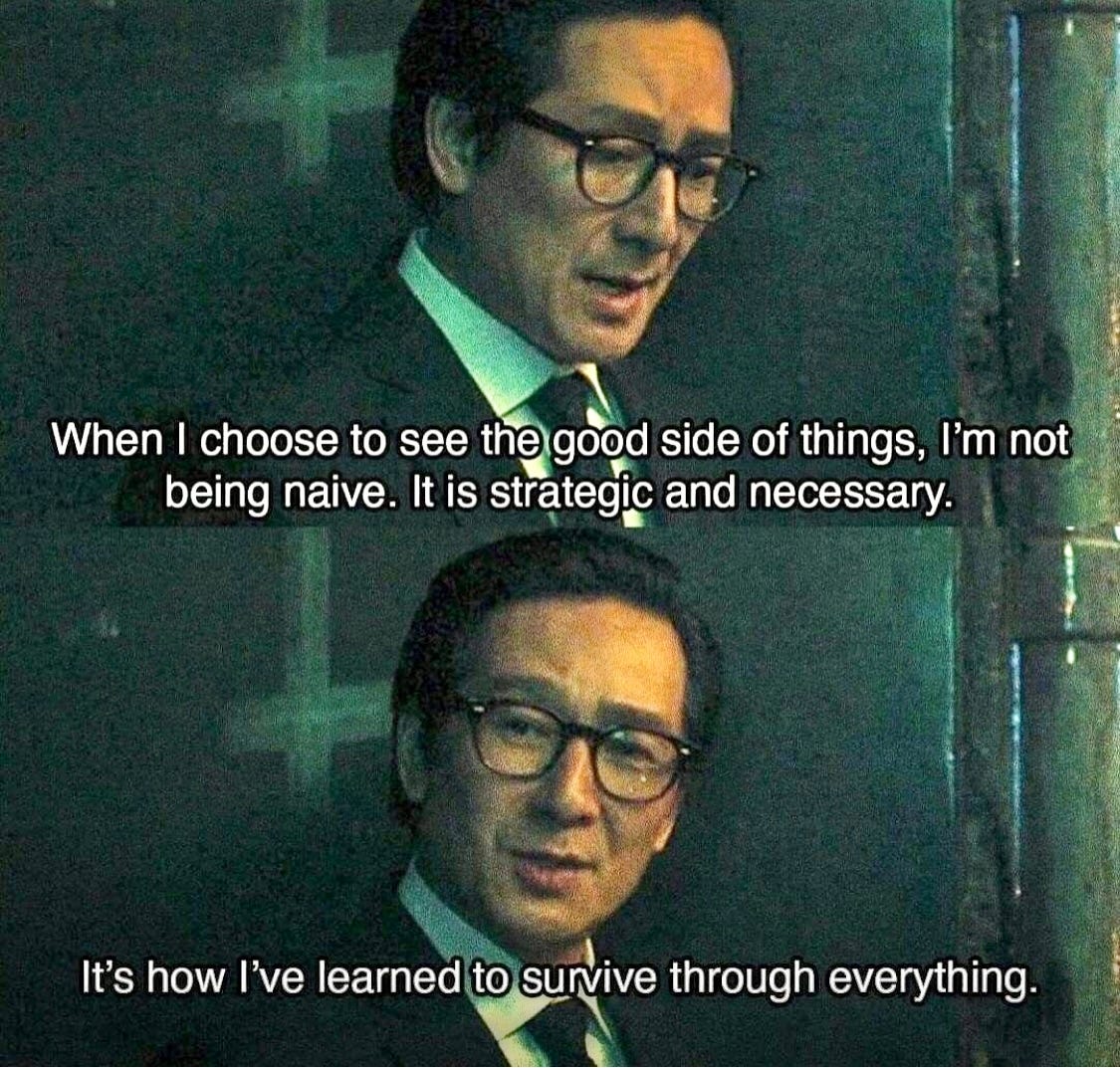

At first glance, it may seem like a coping mechanism to balm any and all disappointment about the real world – to protect oneself from the ills, uncertainty, and unpredictability of human nature. On closer, nuanced inspection, it’s rather strategic: it’s their way of reducing or mitigating the influence of the never-ending negativity on their soul®, ie, they choose not to let it bother them. This doesn’t mean they outright deny its existence, but merely navigate its presence with an elegant nonchalance, allowing them to focus on what makes man good, and to provide platforms to meet them at that standard in their various interpersonal interactions and dealings.

Not Ignorance, but Prudence

In The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902), William James says a “healthy-minded individual” will do whatever he can to minimise the suffering in his life, while a “sick-souled individual” amplifies the bitter truths they encounter and internalises the “wrongness” of the world. To successfully become the former is to shun any influence of evil (used loosely herein) around oneself because he believes every man, deep down, aspires for goodness both within himself and the world around him. I wouldn’t fully liken this to belonging under the Aristotelian umbrella of Eudaimonia, but it’s a close parallel1.

“We saw how this [healthy-minded] temperament may become the basis for a peculiar type of religion, a religion in which good, even the good of this world’s life, is regarded as the essential thing for a rational being to attend to. This religion directs him to settle his scores with the more evil aspects of the universe by systematically declining to lay them to heart or make much of them.” ~ Lectures VI and VII

Humans are super messy and highly ironic. They contain multitudes and severe nuance, which cannot be boiled down to a single action or decision (or a tiny collection of them) made in haste or when subjected to the circumstances they exist in. To automatically assume malice and forever view them under that microscope is myopic. Statistically speaking, you’re going to be much happier assuming people around you are generally good than otherwise; it’s less of a headache, at the very least2.

“The method of averting one’s attention from evil, and living simply in the light of good is splendid as long as it will work. It will work with many persons; it will work far more generally than most of us are ready to suppose.” ~ Lectures VI and VII

Hope as a precondition

Sure, there’s an argument to be made if proven consistently wrong about one’s capacity to strive for said goodness, but within reason, you should definitely try – and you can decide when’s a good place to stop (hence the “as long as it will work” above). To push the limits of this stopping point requires a strong dosage of Hope® in humanity.

“A man who’s willing to break the rules can’t imagine someone else wouldn’t.” ~ Suits, S1E9

This way of viewing the world works here too: you can either seek the goodness in others and strongly believe people seek it in others OR you can seek the goodness in others while hoping they do, but not expecting them to. If you live life believing the former, you’re kinda in for a world of pain when proven wrong – but perhaps, that’s a necessary rite of passage.

I’ve come to notice that the same friends who indiscriminately seek the goodness in others are very hopeful people. Hopeful for the future, hopeful for the people in their lives and their many successess and victories, hopeful that things will be better tomorrow – and I admire them deeply for it, and a few names come to mind. I’ve realised it’s an active choice born out of some comfort in your own skin, a self-assured state of calm that disallows you from projecting your inner evil (or lack of hope) onto others, and consequently, judging them. The strong sense of hope and yearning for inherent goodness isn’t naive, but strategic3.

The caveat

Before you jump at me for being so naive and stupid, there’s a certain nuance in the takeaway here: instead of converging to this idealistic behaviour by living in ignorance about the state of the world and the people in it, it seems wiser to instead cultivate the ability to view the world through a composed lens that allows you to focus on the good by default; it doesn’t hide the evil but merely blurs it out of focus – it’s still there, but doesn’t take up much mental bandwidth or weigh you down. James’ caricature of the “sick soul” instead harps on the harsh truth, allowing it to envelope and occupy their mind.

What’s cool about building a temperament to modulate how well you do this is that several major religions around the world have come to see it as a wonderful aspiration instead of myopically preaching pure ignorance and hatred of evil:

The Greeks call it sōphrosynē, the state of inner harmony that allows you to moderate the impact of the happenings around you. It alludes to sound-mindedness and self-control.

Verses 12.13 and 12.14 (among many other synonymous verses) in the Bhagavad Gita exemplify equanimity and detachment from judgment about events and people around you, which stems from ego.

The Sermon of the Mount from the Gospel of Matthew talks about forgiving endlessly, with a refusal to be poisoned by evil. By “blessed are those who mourn”, the subtext refers to an act of mourning about the state of the world that pushes one towards compassion and seeing the goodness in others.

A hilarious, modern-day rendition of this is learning to be immune to unintentional rage-baiting from your bros, not because you see them as less, but to assume that is not their primary aim when doing something. If it is and you remain unfettered, they’ve failed to elicit any reaction from you, and if it isn’t, that’s one judgement less being thrown around.

I think it’s easy to conflate this tendency with over-empathy, which is further related to having no boundaries for yourself. I think it’s very possible to have healthy boundaries, indiscriminately seek the goodness in others by engaging your own defenses against any discord4, exercise empathy, and remain aware of the peoples’ true aims.

Ultimately, I like to think of this as a force-field, not a fortress, in that you’re not putting up walls against (accidental) preemptive strikes from the people around you, but even if something were to happen, you remain unaffected and ever-hopeful that those around you strive for the highest goodness in their own way. Also, a fortress keeps you fixed and immobile while a force-field (think Holtzman shield from Dune) allows you to be flexible and nimble; it’s a pretty cool analogy IMO.

I know, it sounds vauge and overly idealistic, but I’ve had the good fortune of seeing it firsthand amongst my closest friends, giving me hope in turn 😌

If you’re interested in AI and tech, consider subscribing to my tech blog too:

Eudaimonia refers to living life to one’s full potential in adherence to virtue and reason. What I refer to as “seeking the good in others” can be associated with such virtuous behaviour, but you don’t necessarily have to do that to be considered virtuous. Reluctance to do so comes from various sources (trauma, experience, disappointment, moral injury), but again, doesn’t say much about your inherent sense of virtue. Also, eudaimonia stems from virtue ethics, while “seeking the good in others” is just a practical way of living life to decrease suffering and ruminating.

There’s also the Adlerian perspective of humans choosing to be sad and angry about things, instead of the circumstance demanding sadness/anger to be the necessary emotion someone must equip to navigate it. This take is popularised by fun works like The Courage To Be Disliked.

There’s also the other argument of “they only wish to see the goodness in others because, deep down, they hope someone can do the same for them”. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that either. It’s very easy to believe that those around you are also like you, in that they too, look for goodness in you and others. As with all things, calibration and balance are key.

Not to be misunderstood as having your guard up or raising your walls. Your aim shouldn’t be to protect yourself in the first place, but to disallow anything from harming you.